Kristin Skare Orgeret, Oslo Metropolitan University

The past year has been the deadliest for journalists since the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) began tracking fatalities in 1992. Since 7 October 2023, at least 146 journalists have been killed in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel, and Lebanon, though the actual numbers are likely much higher, as the CPJ is investigating numerous unconfirmed reports of other journalists being killed, missing or detained. Meanwhile, foreign journalists are denied access to Gaza by Israeli authorities.

Recently, Arne Jensen from the Association of Norwegian Editors and I attended The Cairo Media Conference at the American University in Cairo to discuss challenges of war and conflict journalism with journalists and academics. We encountered profound dedication and enthusiasm, but also a sense of powerlessness, anger, and despair over the dire situation in the region.

“The atrocities in Gaza and Lebanon challenge our shared humanity and test the ethics of journalism,” said Nidal Mansoor, from the Center for Defending Freedom of Journalists in Jordan. He added that “the international legal system has collapsed, and journalism is collapsing with it.”

While we were in Cairo, the UN reported that children aged 5 to 9 make up the largest group of the then 43,500 people killed in Gaza. On average, more than 40 children have been killed daily for over 400 days. How do we process such horrifying statistics? How can journalists cover them?

The training of journalists in safety and security is also facing unprecedented challenges. What advice can we give to journalists operating in situations where mere existence is life-threatening? How do they deal with the unavoidable trauma of reporting on conflicts like this?

Refugee journalists

Two experienced Egyptian journalists and security trainers, Noha Lamloum and Cherine Abdel Azim, were at the conference. They have conducted numerous courses for journalists across the Middle East, and they now work with a group of female journalists from Gaza who have fled to Egypt – 12 women, most of whom have lost everything, including their families and children.

Some of these journalists escaped with small children who cower in fear at any loud noise. These women’s most fervent wish was simply to see the sea. Sitting silently with them on the beach, gazing at the same sea that once bordered their homeland before it was devastated, was profoundly moving.

When the women began to recount their stories, it was as though a floodgate opened – words, tears, and emptiness poured out. The trainers were deeply affected themselves, as are many journalists covering the human suffering. “I live off words,” said one of them. “They were my tools, my joy, but now they bring no comfort. They feel increasingly hollow.”

Journalistic double standards

Ten years ago, in January 2015, many of us proclaimed “Je suis Charlie” in solidarity after the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris. Where are the voices now for Hamza, Mustafa, Rami, and other journalists who have been targeted and killed?

“Where is the West?” This was a central theme. Where is the international community? Why the glaring double standards?

The violence in Amsterdam on 7 November 2024 between Israeli Maccabi Tel Aviv soccer fans and pro-Palestinian groups was a case in point. Media outlets failed to report that Israeli fans first burned Palestinian flags and shouted inflammatory slogans. Instead, the narrative focused on anti-Semitism driving the violence.

Zahera Harb, a former journalist from Beirut, now at City University in London, highlighted how UK broadcaster Sky News initially covered the provocations of the Israeli fans, but later replaced the segment with an edited version which largely omitted footage of their provocations. Instead it featured statements from Dutch and British officials condemning anti-Semitism. Sky News stated that changes to their coverage were made to meet their standards of “balance and impartiality”.

However, this is not an isolated incident. Insiders at Germany’s public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, and at CNN and the BBC, have recently spoken out over similar double standards, many of which are ingrained in the editorial guidelines that govern their newsrooms.

“Is it Europe’s lingering guilt over the Holocaust that continues to paralyze its response?” asked one prominent editor in Cairo. “It’s horrifying to think that the victims of hatred and genocide in Europe are now implicated in the suffering of another people. The term ‘anti-Semitism’ has become a trump card, nullifying ethical journalistic standards.”

Is Western media failing?

Western media, guided by balance and impartiality, excels in many areas. However, the extremity of the war in Gaza raises questions about whether the pursuit of balance sometimes impedes the pursuit of truth.

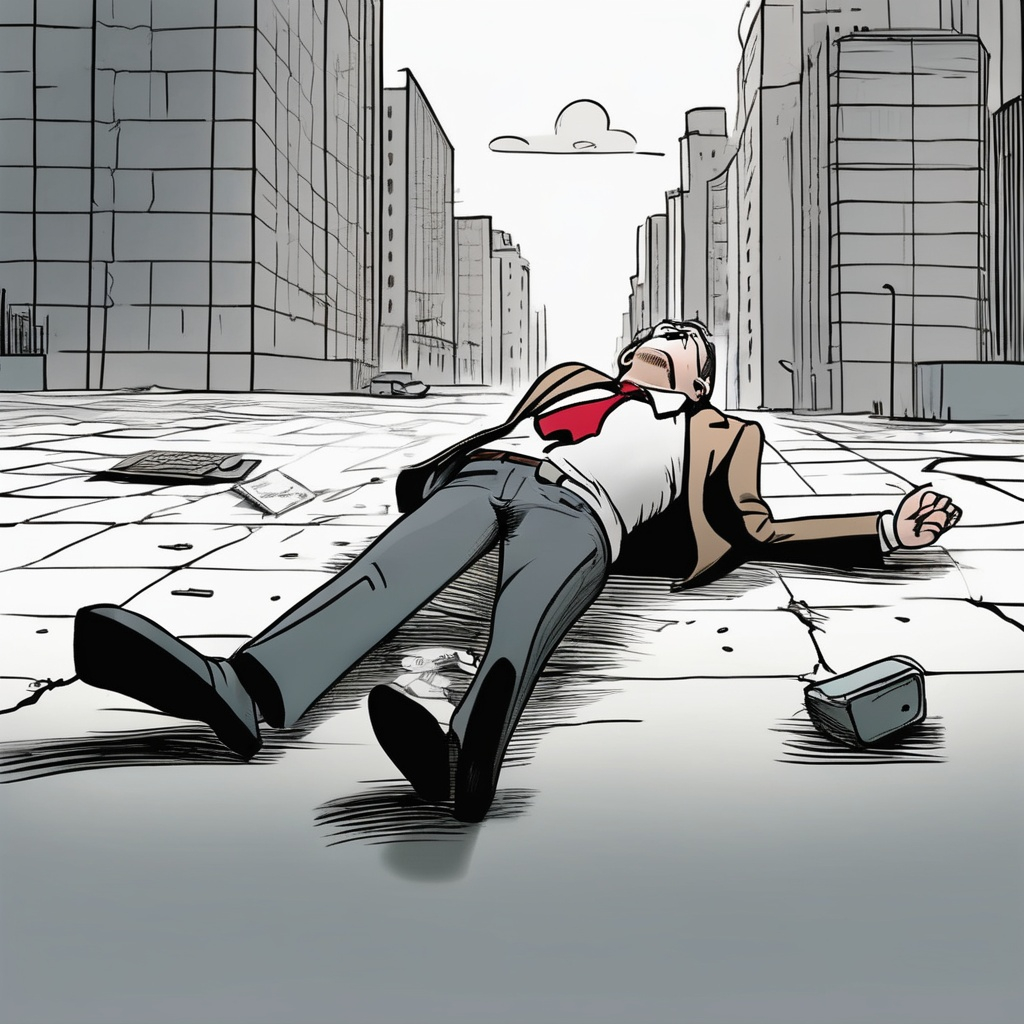

During our discussions with journalists in a region ravaged by mass civilian casualties and direct attacks on reporters, our input on war imagery and hate speech felt somewhat inadequate, a token gesture akin to offering inflatable armbands to someone drowning in a violent hurricane.

“Show the pictures of the dead children,” urged a young female journalist who had been in Rafah. “Consideration for the survivors is a luxury we cannot afford,” said an editor, alluding to the difficult ethical discussions in Western newsrooms about what to publish. These debates highlight the gap between young people’s unfiltered reality on platforms like TikTok and the more curated coverage by traditional media.

It is worth noting that “Western media” is a potentially unhelpful category. In Norway, for instance, we pride ourselves on consistently ranking highest in measures of freedom of expression and media independence.

Our ongoing research (Riegert & Orgeret, forthcoming) highlights the exemplary efforts of Norwegian journalists in their coverage of the October 7 attacks on Israel and the subsequent war in Gaza and Lebanon – they have verified facts, demonstrated methodology, and offered essential context. Many Norwegian correspondents have shown the human side of suffering, and collaborated courageously with journalists on the ground.

Yet difficult questions linger: How are we using our freedom? What can we do when our journalistic tools are insufficient against the horrors of relentless war and potential genocide? More than 60 years after Hannah Arendt documented Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem, her reflections on the banality of evil remain disturbingly relevant.

Kristin Skare Orgeret, Professor of Journalism and Media Studies, Oslo Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.